NEW YORK — It’s been just over 180 days since Marriott International acquired Starwood Hotels & Resorts, but the world’s largest hotel company is not wasting any time. Marriott’s three-year growth plan, announced at its recent meeting with security analysts and institutional investors at the New York Marriott Marquis, includes opening approximately one hotel every 14 hours around the world.

The plan for hotel growth is just part of Marriott’s long-term strategy, which focuses on 2019 but looks well beyond to a future that includes RevPAR growth, further integrating Starwood into Marriott’s world, room growth and careful considerations of both more M&A and organic growth.

Careful Predictions

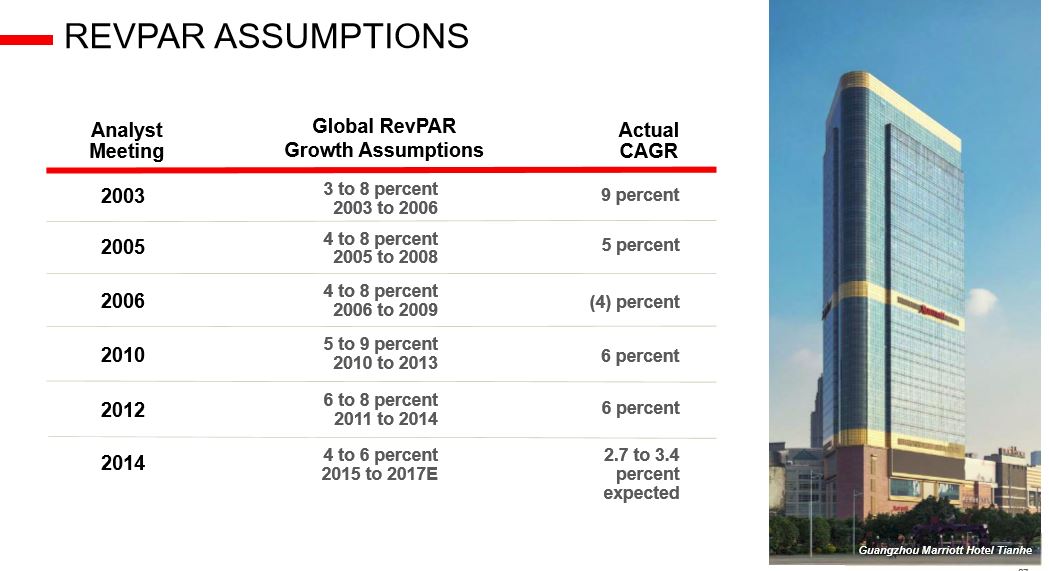

It is, of course, impossible to predict what will happen three years in advance, and Marriott CEO Arne Sorenson advised the gathered analysts and investors that previous assumptions had missed the mark, for better and for worse. In 2003, the company's global RevPAR growth assumption for that year through to 2006 was 3 to 8 percent, and the actual final CAGR was 9 percent. But by 2006, with a global RevPAR growth assumption of 4 to 8 percent for that year to 2009, the global financial crisis dealt a blow and the actual CAGR was -4 percent.

Since then, the actual CAGR for the three-year growth assumptions presented at the analyst meetings have fallen within the assumed ranges, although the final results from this year may fall below the three-year assumptions made in 2014.

The latest assumption is tentative, with scenarios of 1-3 percent global RevPAR growth compounded from 2016 to 2019. (Sorenson was quick to note that these numbers were not forecasts or guidance, but “reasonable bookends” to calculate how business may look under different conditions.)

How Starwood Changed the Game

The Starwood acquisition took Marriott from operating in 87 countries and territories at the end of 2015 to having a presence in 122 by the end of 2016. The combined company now controls more than 8 percent of the world’s hotel rooms, including existing hotels and the signed new construction pipeline.

Starwood, Sorenson said, is not only the largest acquisition but “the most dramatic change” in Marriott’s history. “Our decision to acquire Starwood was rooted in a simple idea: By acquiring a company with Starwood’s depth and breadth, we could offer guests and hotel owners the broadest distribution, the strongest brands, the most powerful loyalty programs, and the most innovative services in the industry.”

In the 180 days since the acquisition was finalized, Marriott has linked its Marriott Rewards loyalty program with Starwood’s SPG program, integrated its development organization and rolled out its unified guest feedback system, guestVoice, across legacy Starwood properties.

Still, Sorenson said, there is a lot of work to be done. “On April 1, we expect to bring U.S.-managed Starwood hotels to our financial back-office platform. Will also begin to integrate sales effort by aligning sales execs for our largest 750 global corporate accounts.”

In the short term, over the next five weeks, legacy Starwood hotels will begin to see lower prices from Marriott’s procurement programs as well as lower commissions from the company’s OTA contracts, Sorenson said.

Driving RevPAR

Looking farther ahead, the combined companies’ financial reporting infrastructure should be integrated in early 2018, and the reservations and loyalty platforms should be complete in late 2018.

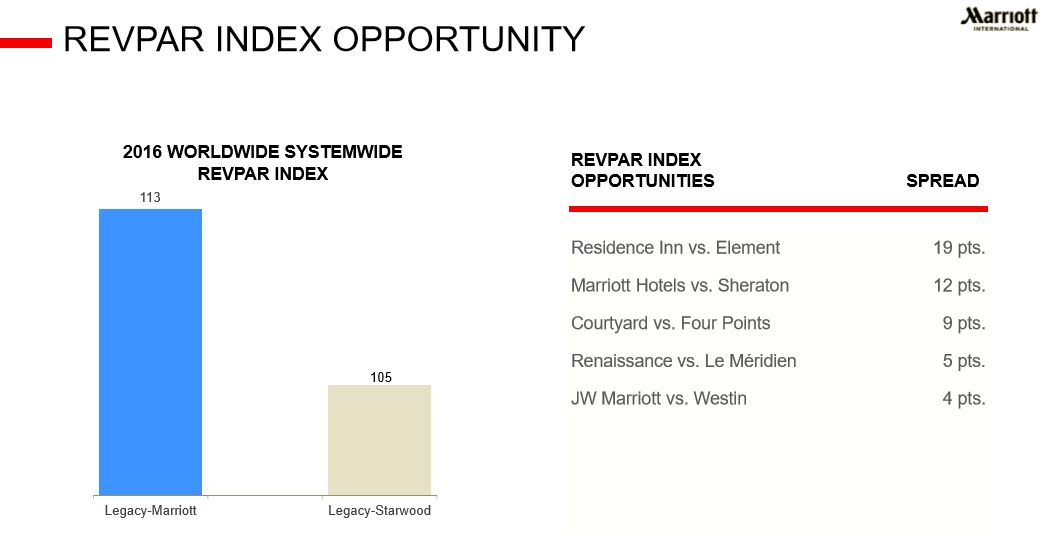

On average, the legacy Marriott portfolio of brands had RevPAR index of 113 in 2016, meaning that the hotels’ RevPAR on average ran a 13 percent premium above their competitive sets in each market. On average, the legacy Starwood portfolio brands had a RevPAR index of 105.

“We believe we will improve the Starwood RevPAR index given the power of our loyalty programs, scale in sales and marketing and operating expertise,” Sorenson said. “We don’t expect that growth to come at the expense of our legacy Marriott brands. In fact, we believe there is opportunity for further Marriott RevPAR index improvement as our larger system drives larger share of wallet.”

In the long run, he said, scale and RevPAR should drive profit for both Marriott and Starwood brands.

Room Growth

Through 2019, Marriott expects to see 285,000 to 300,000 gross room additions for a worldwide total of 1.4 million rooms across its 30 hotel brands. On a net basis, Sorenson said, this represents 6.5 percent net compounded room growth, compared to a 5-percent annual compound rate over the last three years (including the legacy Starwood brands). “Our unit growth is accelerating with little of our capital, largely due to a successful franchise development strategy in North America and meaningful management contract growth in international markets.” A full 95 percent of the rooms in Marriott’s three-year growth plan have already been identified, he said.

These new rooms could yield a record $675 million in annual stabilized fees, Sorenson said, non-property related franchise fees (largely credit card branding fees) should increase by $100 million during the three years.

M&A vs. Organic?

While a new hotel every 14 hours is a lofty goal, Marriott is not planning to make it happen by acquiring another major company anytime soon. “The Starwood acquisition is quite different from any transaction we’ve ever done,” Sorenson said. “It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to remake the company and make a significant strategic leap forward in distribution and scale. I doubt you will see Marriott do another deal like it for a very long time.”

Mergers and acquisitions, while helpful, should not be a company’s sole means of growth, Sorenson said. Organic growth, especially for select-service and extended-stay franchises, is “nearly free.” At the higher end of the market, in the luxury and lifestyle segments—“where brands drive true customer passion and construction costs are higher”—organic growth can be a bit more expensive, he said, but is still a solid option.

So why shouldn’t Marriott—or any hotel company—only expand organically? “Sometimes, M&A is just compelling,” Sorenson said. “Adding a strong brand at a reasonable price to a powerful portfolio can be more valuable than starting from scratch, particularly for new brands at higher price points.” M&A drives scale, he added, and scale drives new development.

In contrast, organic growth can take time, and the slow process means that scale advantages are delayed or never achieved. The owner returns are less attractive, and new development is more challenging, especially in the luxury and lifestyle segments..

On the other hand, while an M&A deal may need more upfront capital, new construction isn’t cheap. “We’ve seen that owners of hotels developing new organic brands expect discounts on management or franchise fees if they are taking a capital risk on an unproven brand,” Sorenson said.

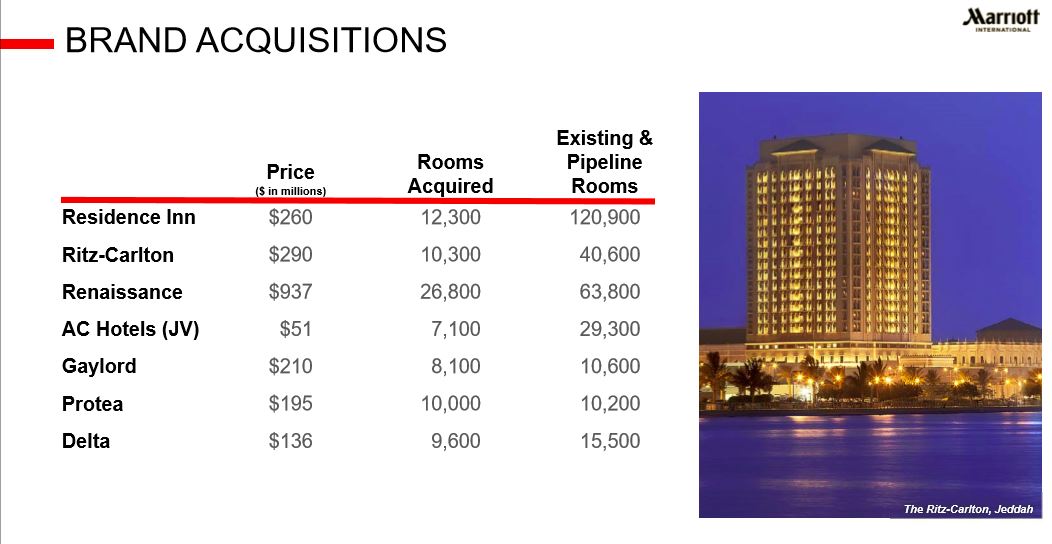

Marriott’s M&A experiences in the past have been “very good,” Sorenson said. By acquiring brands over the years, Marriott has been able to gain footholds in growing markets and partner with established professionals who already know the terrain.

And while these acquisitions contributed to Marriott’s room count, Marriott has helped the brands grow as well. The extended-stay Residence Inn brand is now 10 times its original size, while Ritz-Carlton and AC Hotels have both quadrupled and the Renaissance brand has doubled. By acquiring the South African Protea brand in 2014, Marriott now has nearly 9,000 rooms in the Sub-Saharan pipeline across 13 brands, which would have taken years without Protea’s presence.

Still, Sorenson said, Marriott did not acquire these brands just to get rooms. “They each provided an immediate strategic fit that would have been time-consuming to solve with existing brands or creating one from scratch,” he said.

As such, a hotel company should not necessarily completely exclude organic or M&A growth. “Both can be, and have been, compelling,” he said.