Hotel investment in Africa is on a steady incline. In April, W Hospitality Group reported that there were 64,000 planned rooms (365 hotels), representing 36 hotel chains and 86 brands, in Africa. This represented a more than 40-percent increase over 2015.

As this investment push accelerates, it is worth looking closer at a concept that could serve as something of a lens for uncovering additional investment opportunities—the value chain.

The term “value chain” is ubiquitous in the consulting world, especially pervasive with regard to manufacturing and services. Analyze the value chain for a particular industry, especially tourism, and, voilà, you are possibly unlocking the secrets to a new universe of solutions for attracting investment, reducing poverty, generating employment and everything else that is supposed to make the world a better place.

The Value Chain Origins

Harvard University competitiveness guru Michael Porter popularized the concept in his 1985 best seller, “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.” He first thought about the concept as it related an individual company, but later realized that the notion could be applied to entire countries and particular industry sectors, such as tourism.

In Porter’s book, “The Competitive Advantage of Nations,” published five years later, he applies the concept wholly to countries. He sees a country’s competitiveness through a series of links—for example, purchasing a tour package and the delivery of services and experiences that comprise the package—that fit into a chain of value for both suppliers and buyers.

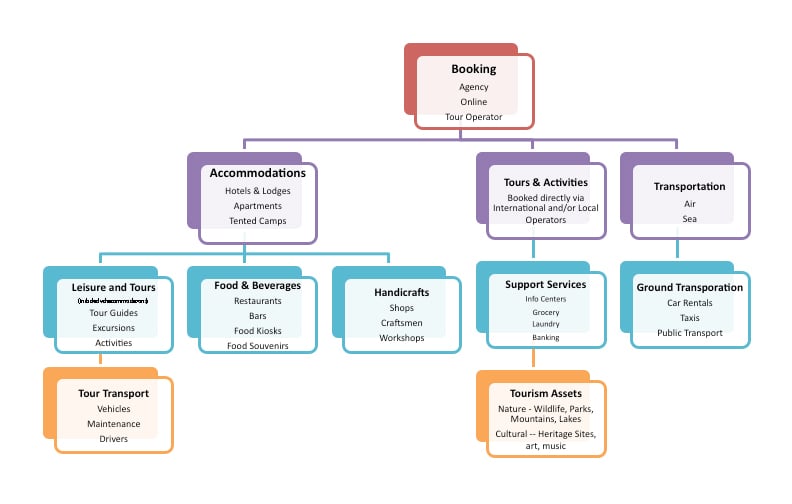

I was asked recently to shed some light on what this means for Tanzania, a country wherein tourism is the largest services sector and one of its fastest-growing sectors. At a macro level, the tourism value chain looked like the following diagram:

For people working in tourism, none of this should come as a surprise. In the above diagram, each component is in itself a value chain with a potential set of backward linkages. For example, the value chain for leisure and tours could involve vehicle purchases or rentals for the tour, maintenance of the vehicles at an auto shop, hiring drivers and guides and contracting with local operators for the tours. In this example, a typical visitor would book a package that includes accommodations, full board and tours with air fare booked separately. Alternatively, the visitor might book only tours and/or only air fare. Guests in the accommodations generate demand and thus spending for activities, tours, food, beverages, handicrafts, the support services and ground transportation—all of which, of course, requires production and delivery.

For Tanzania

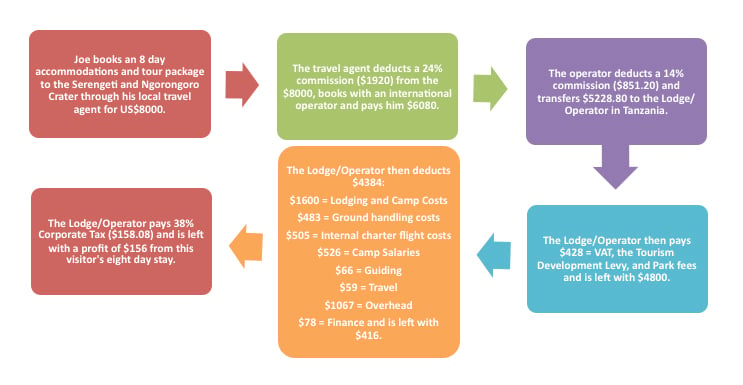

In the case of Tanzania, a fast-growing destination for tourism, though somewhat slower for investment, tourism earns more than any other export services sector and, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council, generates more than 1 million jobs in the country. The following is an actual example from a major lodge operator in Tanzania:

Of the original $8000 price, $5228.80, or 65 percent, enters the country. And, of the latter amount, all but $156 (profit) is spent on local operations, wages, activities and supplies, thus payments into the local economy. Moreover, local hotels and restaurants are more apt to use local supplies if they prove to be cheaper and as reliable as imported items.

For lodge owners, this could mean tight margins, but it also means there are incentives for investing in other parts of the value chain to increase margins. In other words, it behooves the lodge owner to also invest in the tour operations, local food, crafts production and transport. Companies such as lodge and tour operator Nomad Tanzania recognize this and insist on investing in and supporting local community development and conservation efforts, such as:

• Micro-finance loans for their local guides to buy their own safari vehicles. They then hire the guides and their cars, allowing them to earn double.

• Internal staff development and promotion so that all have the opportunity to realize their own ambitions within the company. Some of their guides, for example, started as waiters or room stewards.

• Rigorous guide training for both old and new guides to advance their knowledge of wildlife skills, bush craft, photography and basic hospitality skills to make them amongst the best in the African safari industry.

• Concession fees are paid to Nduara Loliondo, a Maasai community area that serves as an important buffer zone bordering the Serengeti National Park to ensure that wildlife can move unhindered through the area. This helps create an incentive to look after the game that passes through.

• Home-grown veggies: In the remote Mahale Mountains, the locale is a 24-hour ferry journey from the nearest town (or a 4-hour flight), where most of their camp food comes from. Through the Nomad Trust, they set up a near-by community vegetable garden, which now supplies most of their vegetables, and provides a valuable local income.

• Support for local organizations and businesses: Most of the furniture in their Lamai locale, for example, was made by a company that has been training up former street kids to become expert carpenters.

Other operators and organizations are conducting similar efforts throughout the country. Tanzanian operator, Classic Tours & Safaris, and international operators, such as Micato, Overseas Adventure Travel and Abercrombie & Kent, also include community support, as well as community visits in their programs. Emanuel Mollel, Secretary General of the Tanzania Tour Guides Association, explained that tourists now coming to the country want more than the traditional safari experience, “They want to interact with local communities.”

From Harvard to the villages of Tanzania, there are myriad links that make up a typical tourism value chain—and many opportunities to make the most of a tourism investment and conserve cultural and natural heritage.

| Scott Wayne is the president of SW Associates, a Washington, D.C.-based sustainable tourism consultancy, focused on strategic planning and investment for destinations on every continent. For further information: www.sw-associates.net and [email protected] |