Earlier this year, I was on a field mission in Tanzania and Zanzibar for the World Bank. The purpose was to explore ways that tourism could help benefit and generate profits for the country.

While there, the Hotels Association of Tanzania (HAT) told me about one of their biggest concerns: Airbnb. Yes, the same home-sharing site that was ubiquitous in North America and Europe was now, too, stretching its sharing economy arm into Africa.

Specifically, HAT was concerned about the rapid rise of Airbnb rentals in the country. They were concerned that these accommodations could operate without the many licensing, registration and taxation requirements of formal accommodation establishments, thus undercutting the prices of their members’ establishments. A visitor now has a choice of over 300 Airbnb registered properties in Tanzania and Zanzibar that include a luxury beachfront villa in Zanzibar and a beautiful country home near Mount Kilimanjaro. They wanted to take action, but were not sure what to do. And the government was not yet considering this an issue.

The Airbnb Impact

We have been tracking the impacts of Airbnb on the tourism industry, especially on hotels, over the past year. HAT’s concerns are not surprising; they are echoed by many municipal authorities around the world, which see the proliferation of unlicensed Airbnb accommodation providers as reductions in licensing and tax revenue. Another concern is that Airbnb rentals are reducing the number of available units of affordable housing in cities such as New York and San Francisco.

In Tanzania, as well as in several other countries that I have recently researched—Cape Verde, Cyprus, Uganda, Armenia, among others—Airbnb providers were not required to be licensed as formal accommodations establishments or pay the same level of taxes and fees, if any at all. The situation, however, is very fluid and destination authorities seem to be catching on to requiring some degree of taxation.

In the U.S. and Europe, municipal authorities and hotel groups in several cities began to complain about what was perceived as unfair competition and declines in revenue. So Airbnb began collecting taxes from customers on behalf of selected U.S. municipalities (i.e. those that requested it) and then passing on the amounts collected to the municipalities, a process that is now a standard Airbnb offer. The questions and complaints from municipalities had mushroomed over the past years prompting Airbnb to launch a public policy and “global civic partnerships” team and this is who runs it.

Airbnb’s official policy is: “In those places that respect the right of people to share their home, we will work to ensure that the Airbnb community pays its fair share of taxes while honoring our commitment to protect our hosts’ and guests’ privacy. This includes helping to ensure the efficient collection of tourist and/or hotel taxes in cities that have such taxes. We will work to implement this initiative in as many communities as possible.”

In their “Community Compact,” Airbnb states they help create “economic opportunity.” Their data show that “the typical middle-income host in the United States can earn the equivalent of a 14-percent annual raise sharing only the home in which they live...Airbnb democratizes travel so anyone can belong anywhere—35 percent of the people who travel on Airbnb say they would not have traveled or stayed as long but for Airbnb.”

Several interesting studies appeared in 2015 and 2016 that have tried to examine Airbnb’s economic and revenue impacts in destinations. It is not clear whether Airbnb customers would have selected formal accommodations instead of private accommodations. One thing is clear: Airbnb customers are staying in neighborhoods that would not usually attract visitors. They are helping, then, to disperse overnight visitors to more communities within a destination town or city.

A May 2015 Boston University study, “The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry,” found in analyzing the Texas hotel market that revenue of “the most vulnerable hotels” decreased by 8-10 percent since 2010 due to Airbnb. In fact, they found that, at least in Texas, each additional 10 percent increase in the size of the Airbnb market resulted in a 0.37 percent decrease in hotel room revenue.

In January 2016, Penn State University School of Hospitality Management published a study titled “From Air Mattresses to Unregulated Business: An Analysis of the Other Side of Airbnb,” which was funded by the lobbying arm of the hotel industry, the American Hotel & Lodging Association. The survey analyzed hundreds of thousands of data points that revealed "an alarming trend.”

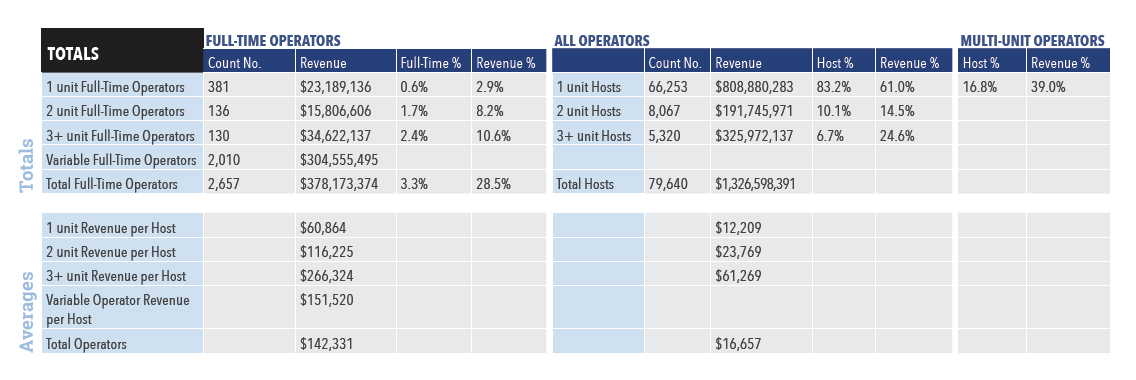

Multiple-unit operators who are renting out two or more units, and full-time operators who are renting their unit(s) 360 or more days per year are generating a substantial amount of Airbnb’s revenue. Hosts who rent fewer than 360 days, but still far more than occasionally (for instance, more than 180 days), also contribute greatly to Airbnb’s bottom line. In fact, the multiple unit operators account for 40 percent of Airbnb’s US$1.3 billion in revenue in the 12 cities studied. Nationally, the study found that the “mega-operators (those renting out three or more units) grew the most, increasing from $16.1 million in September 2014 to $29.2 million in September 2015, an 81.4 percent increase.” The number of these operators increased from 1,171 to 2,193 in the same period, an 87.3 percent increase.

The following table summarizes some of the data from the 12 cities studied:

Airbnb published its own mini-study in 2013 showing the economic impact of their rentals on New York City, as well as in a number of neighborhoods. From their analysis, they estimated that 416,000 Airbnb visitors generated US$632 million in a year. They also showed that 82 percent of the properties were outside of mid-Manhattan. In the outer boroughs, US$105 million was generated supporting 950 jobs.

The rapid rise of Airbnb rentals in New York City and the state prompted New York State legislators to pass a bill in June 2016 that will “heavily fine hosts on Airbnb and other short-term rental sites for allowing listings by hosts of rentals that violate the state’s short-term rental laws.” Assembly member Linda B. Rosenthal, a sponsor of the bill, said that “[It will]…crack down on illegal hotels that destabilize communities and deprive us of precious units of affordable housing.” Airbnb protested the bill claiming that it would negatively impact tax revenue and hosts that use the service to supplement their incomes.

From an overall tourism perspective, Airbnb is providing a great service of dispersing visitors into neighborhoods that usually do not benefit from visitor spending. The New York example is repeated around the world.

The full time and mega-operators are, however, a legitimate concern for the hospitality industry. These operators are essentially operating accommodation businesses similar to more formal lodging. And yet they are not subject to the same licensing and registration requirements and thus operate at a considerable competitive advantage compared with the formal accommodations. Leveling the playing field by establishing clear standards and legal requirements for short term rentals, including some degree of taxation, would seem to be a fair solution.

In some parts of the world, formal accommodation providers are also taking advantage of the wide customer reach of the Airbnb platform to help fill beds in slower periods. In Tanzania, for example, a few safari camp operators are using Airbnb to help fill unsold beds. While this detracts from the original sharing economy philosophy of Airbnb, this could be a good hybrid solution for some accommodation providers, especially in emerging markets such as Tanzania. Airbnb, after all, is nothing more than a distribution platform—why not take advantage?

This story is far from over. Expect to see the continued rapid expansion of Airbnb rentals around the world and continued puzzlement from government authorities as to how to minimize the negatives and maximize the benefits.

Scott Wayne is the president of SW Associates, a Washington, D.C.-based sustainable tourism consultancy, focused on strategic planning and investment for destinations on every continent. For further information: www.sw-associates.net and [email protected]